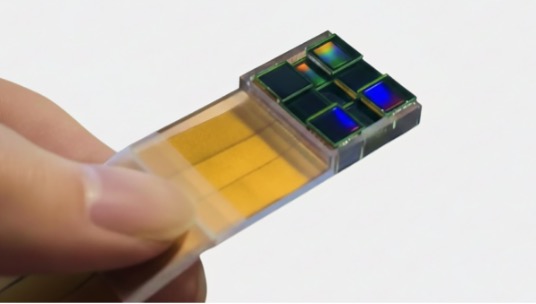

Researchers at the University of Connecticut announced something that sounds impossible on January 11. They built a camera that takes sharp images without using any lenses called as MASI. The Multiscale Aperture Synthesis Imager (MASI) turns this challenge on its head. Rather than forcing multiple optical sensors to operate in perfect physical synchrony. It is a task that would require nanometer-level precision. The whole thing sounds backwards, but apparently it works really well.

The team published their results in Nature Communications, and the potential uses are all over the place. Medical imaging, crime scene analysis, quality control in factories. Basically anywhere you need to see tiny details clearly.

Here’s how it works, or at least how I understand it after reading through the paper. Normal cameras need lenses to focus light onto a sensor. The lenses have to be positioned exactly right, and if you want better images, you need bigger, more expensive lenses. It gets complicated fast. This new system ditches that entire approach.

Instead, they use multiple sensors scattered around. MASI lets each sensor measure light independently. Nothing gets focused, nothing needs perfect alignment. Then computer software takes all those messy readings and figures out what the actual image should look like. The sensors collect the data separately, and then uses computational algorithms to synchronize the data afterward.

Guoan Zheng, the biomedical engineering professor running the project, said this solves a problem that’s been around forever in optical imaging. There’s a similar technique called synthetic aperture imaging that radio astronomers use. That’s how they got the first picture of a black hole a few years back. But radio waves are massive compared to visible light, so syncing everything up is way easier. Optical wavelengths are thousands of times smaller, which makes the traditional method nearly impossible.

What makes this new system different is it doesn’t even try to sync things in real time. The sensors just do their job independently, and the computer crunches the numbers afterward. You end up with really detailed images from distances that weren’t possible before, and you don’t need all the heavy optical gear.

Zheng mentioned the tech could show up in forensic labs, hospitals, manufacturing plants, basically anywhere high quality imaging matters. But the part that really stood out to me was the scalability. With regular camera systems, making them bigger means everything gets way more complicated. Adding components makes the whole system exponentially harder to manage. With this setup, adding more sensors is just adding more sensors. The complexity stays manageable.

For Illinois Tech students working in anything related to imaging, computer science or engineering, this shows how sometimes the best solution isn’t improving what already exists. Sometimes you just need to throw out the old rulebook entirely.